Chris Thomson joined the RMI team in November as the newest addition to our Operations department as the Operations Assistant. In this role, Chris is in charge of the daily dispatch of the company’s truck fleet. Chris schedules generator pickups and end user delivers and any other problem that is thrown his way. He is resilient and smart and quickly got the nickname of “Turnip” because they can survive and strive in the toughest of circumstances. Prior to joining RMI Chris served in the military and then spent time as a cross-country truck driver.

Chris Thomson joined the RMI team in November as the newest addition to our Operations department as the Operations Assistant. In this role, Chris is in charge of the daily dispatch of the company’s truck fleet. Chris schedules generator pickups and end user delivers and any other problem that is thrown his way. He is resilient and smart and quickly got the nickname of “Turnip” because they can survive and strive in the toughest of circumstances. Prior to joining RMI Chris served in the military and then spent time as a cross-country truck driver.

Eryka Reid came on board in March as the new part-time Administrative Assistant but is now the full-time Compliance and Marketing Assistant. In these roles Eryka builds maps for all of end user sites and coordinates tradeshows and conferences for the sales team. She is also responsible for maintaining our website and social media sites. Eryka graduated from Plymouth State University with a B.S. in Environmental Science and spent the last year working for Keepsake Quilting, which is a worldwide quilting company. With a science degree and some marketing experience Eryka was a good fit for what RMI needed.

Eryka Reid came on board in March as the new part-time Administrative Assistant but is now the full-time Compliance and Marketing Assistant. In these roles Eryka builds maps for all of end user sites and coordinates tradeshows and conferences for the sales team. She is also responsible for maintaining our website and social media sites. Eryka graduated from Plymouth State University with a B.S. in Environmental Science and spent the last year working for Keepsake Quilting, which is a worldwide quilting company. With a science degree and some marketing experience Eryka was a good fit for what RMI needed.

Matt Nelson is also one of the company’s newest employees having come on board in the beginning of June. Matt has joined our Delivery Team focused on operating the company’s roll-off truck. Matt’s experience ranges from operating the tractor trailer at Lowes to working previously for Caselle.

Matt Nelson is also one of the company’s newest employees having come on board in the beginning of June. Matt has joined our Delivery Team focused on operating the company’s roll-off truck. Matt’s experience ranges from operating the tractor trailer at Lowes to working previously for Caselle.

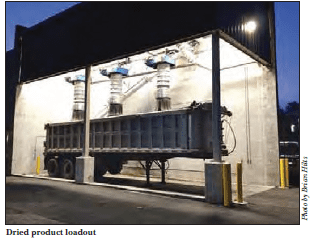

With the new process underway RCSD developed a marketing plan to help identify outlets for the dried product. Hoping for a “turn-key” partnership, in which the partner would take responsibility for the dried products from the loading facility to outlets, that is where RMI comes in!

With the new process underway RCSD developed a marketing plan to help identify outlets for the dried product. Hoping for a “turn-key” partnership, in which the partner would take responsibility for the dried products from the loading facility to outlets, that is where RMI comes in!

Jamie Oliverez will spearhead the NY Region as its manager. Jamie comes to RMI with an extensive residuals management background. He formerly worked for the state of Washington as their biosolids regulator, overseeing all biosolids activities in the state.

Jamie Oliverez will spearhead the NY Region as its manager. Jamie comes to RMI with an extensive residuals management background. He formerly worked for the state of Washington as their biosolids regulator, overseeing all biosolids activities in the state.